Anthology for Listening Vol. II – Paralingual Index

Paralingual Index

Clara Mosconi

Performing language

It’s with a Danish mother and an Italian father that I grew up. I’ve got two siblings. My sister is nine years older than me, and she’s got a different mother than my brother and I have. My sister was born in Italy. Naturally, Italian became her mother tongue and Danish took second place. When she turned four, my father and our sister’s mother divorced, and my sister and her mother moved back to Denmark. My sister started to attend a Danish kindergarten. Later on, she went to elementary school, with the consequence that Danish quickly became her first language. Although my sister’s fluency in Italian has faded over the years, she often surprises me when a situation might somehow compel her to speak Italian. It seems as though the language arises on its own steam, and always at the correct time and place.

My brother is only two years older than me, and we share a similar upbringing. We grew up together in a small suburban town in the middle of Sjælland. Our father owns an Italian restaurant in the centre of town. Seeing as the restaurant generated the only income for our household, my father was always working. It was only seldom that we saw him at home. On the other hand, we spent a great deal of time with our Danish mother. Danish is our mother tongue, and Italian has always been there, but in an incredibly undefined way.

After finishing high school, my brother jumped on the very first flight to Italy. We were all surprised. Back then, he didn’t talk much. He was absolutely shy, but I also think that he simply enjoyed the silence. He moved in with Nonna Rosa and Zia Silvana, our paternal grandmother and father’s sister, in the big pink house on top of the hill in Mondaino, and he took a job in the local factory, where he glued rhinestones onto different types of accessories for large fashion houses. While he sat around the large table, the hours crawled by at a snail’s pace, and there wasn’t much else for him to do than to try and converse with his colleagues. He quickly made good friends. His colleagues came from all over the world, but Italian became their common language. While he was driving home after putting in a long day at the factory, Zia and Nonna were busy making dinner. A new table around which to converse presented itself before him. When I visited my brother, a month and a half after he had moved to Italy, he was already fluent in the language. I had never heard him utter a single word in Italian, and suddenly he was speaking it like he never had before.

My relationship with Italian behaves in an almost mythical way. To be perfectly honest, whether or not I ever spoke Italian isn’t entirely clear to me. As a child, bolstered with uncompromising self-confidence, I was convinced that I could speak the language. I can clearly remember how I demonstrated (performed) my Italian, in order to impress the other kids at school when, every autumn, I would return after spending another long summer in Italy. Convincingly, I rolled my r’s, coloured and conducted the pitch, and softened my double consonants. Perfetto. I wasn’t the least bit conscious about the well-orchestrated performance at that time, but I was absolutely certain about what my ears had heard, and I was the master of imitation.

Recently, I asked my mother what she remembers about my Italian as a child, and she told me about one very specific memory. She was observing me sitting at the dining table in the kitchen inside the pink house in Italy. I was busy drawing a picture, and Nonna, who was otherwise busy with cooking, stopped behind me to see what I was busy drawing. I jovially explained to Nonna what I had drawn. She looked on and nodded in appreciation of my explanation. She asked questions and she pointed her finger, and I responded and explained. My mother remembered my language as a blend of actual Italian and a lot of Italianesque sounds. Our communication took place somewhere between our languages, and a connection was being nourished.

Whether my Italian-sounding language was governed by any system is something I’m decidedly less sure about. However, the sounds came forth with an intention. Clearly, I was delivering a message, convinced that the language was dwelling inside me, somewhere, and I had confidence that the sounds and words that were supposed to communicate for me would eventually spill out.

As time went by and I got older, and generally more and more bashful, my “Italian” actually faded. The summers grew longer. I fell silent. And a growing shame about my lost language came to the fore. I took over my brother’s silence. The fear of making a mistake sat inside me, and I wouldn’t hold a single Italian word in my mouth. My identity came to be embraced by a wordlessness, and things didn’t have any words: no language was connected to them. Instead, they were merely sounds emitted from the mouths of others. I perceived everything in a wordless state of being, in parallel with a language that I couldn’t attain on the same terms as could the rest of my family. Things were sounds, waves, particles. They were nameless, I was wordless.

And at the same time, language was as clear as water. I heard right through the words, without getting captured by metaphors and heavy meanings that were closely attached to what was being spoken. Instead, it was pure, sonic aesthetics. Sounds I had been listening to ever since I was a child. Sounds that had forms and colours: temperaments without literal meaning.

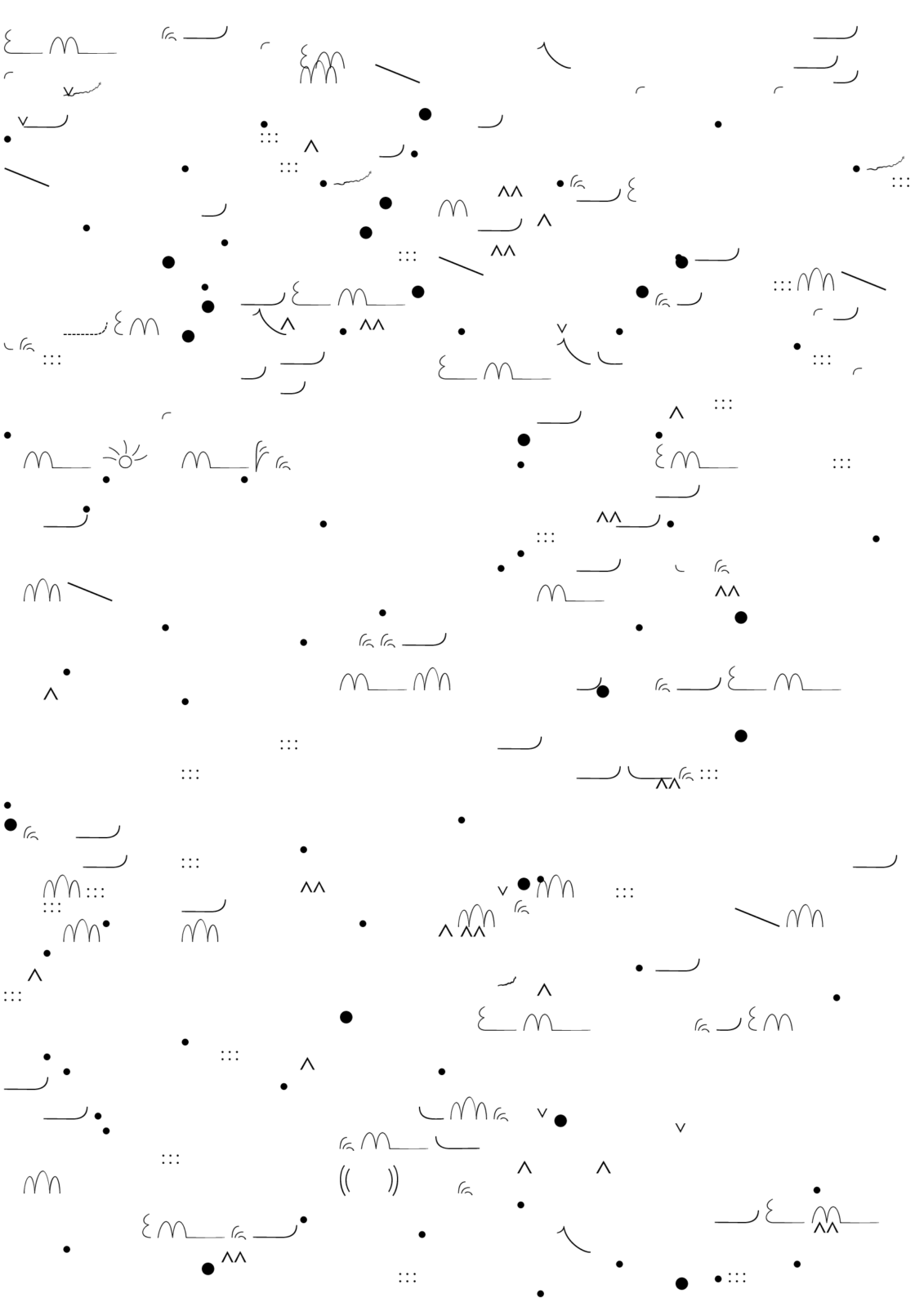

Index

Paralingual Index no. 1 is a collection of 32 symbols invented and designed by Clara. Each symbol represent a non-verbal sound phenomenon – sounds that are often produced when grappling with language in search of the “right” words. The symbols are intuitive in their design, and they refer to the sounds’ performative aspect, how the sounds relate to the body.

The Paralingual Index no. 1 is also a digitized typograph in the form of a font which can be installed on a computer and used on a keyboard. The font is open access and available to everyone. It can be accessed and downloaded at: https://claramosconi.com/Paralingual-Index

Paralinguistics Paralinguistics are the aspects of spoken communication that do not involve words. It unlocks a new potential in communication in that it escapes existing expectations of language. It thrives in the peripheries of language, in the gap between our self and what come out of our mouths, and is perhaps normally perceived as something faulty, or as an excess material within language. Paralinguistics escape the heavy meanings and metaphors that are so closely tied to words, and allow us instead to appreciate the sonic aesthetics of these non-verbal sounds, e.g. the sound and tone of the voice, the color and pitch, the sound of a cough or even the movement of a laugh.

The graphic score has been produced using the symbols from the Paralingual Index. They are simply paralinguistic transcriptions of interviews that Clara have conducted since 2020 with bilingual people. The transcriptions act as a portrait of a language, as well as a graphic score.